money

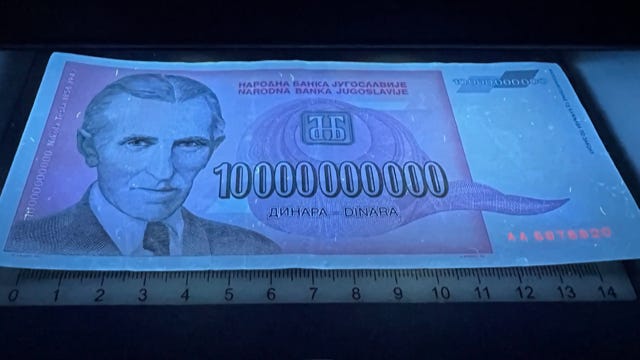

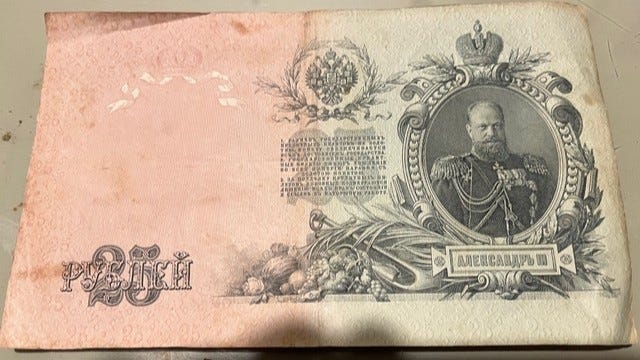

There are two kinds of money: money you have and money you owe. The money you owe is more precious than money you have because more people care for you so that you’ll pay them back. To get your money you must remember your passwords. These passwords are in your phone. When you lose your phone you also lose your money, your pictures, your letters, your friends, your acquaintances, and the institutions that keep you clothed, fed, and sheltered. When you lose your money, your address, your kin, your identification and your writing you become an outsider. Your only hope is that people you owe money to will restore your “personal” data because you must produce what you owe. “Personal” is between quotation marks because you don’t own anything, not even your debt. You have delegated your memory to your device and that device belongs to everyone in it. There is nothing personal about your person, except the quotation marks I just gave you. This is not tragic. The fellow subway riders you join are all trying to find their lost passwords.

When I lived in New Orleans, an unwashed and unhoused guy named John liked to camp on the stairs to my studio. John greeted me with quotes from Shakespeare whenever I came home: “Travelers never did lie, though fools at home condemn them.” One day John said to me, “I used to live here.” I asked, “What happened, John?” “I lost the key.” That could happen to anybody. Look at Ulysses. Or Wakefield. John never asked for money, but I sometimes gave him five 1990 dollars. That would be twenty 2026 dollars now.

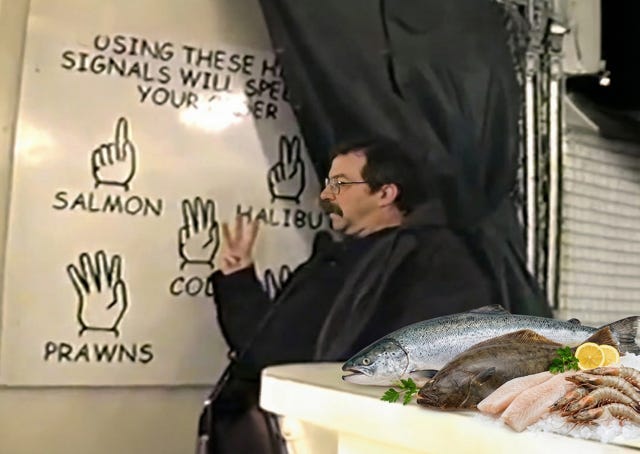

When I moved back to New York I often passed a street-dwelling person, incidentally also named John, who’d set up shop in front of the Food Co-op in Park Slope. He was no Shakespeare John, he asked for money, but would converse if you needed company, and most Co-Op members did, while waiting in line for their discounted food. One day he told me that “there are a lot of writers in Park Slope.” He discovered this while foraging through trash and noticing many discarded drafts of stories and poetry. One day I heard John reading out loud from a paper he’d found. It was some kind of experimental prose. Instead of his usual, “Give me some money!” he started reading out loud every day. He got an audience. At first it was only people in line, then people who came just to listen. They stuffed his hat with bills.

John found more and crumpled and discarded writing he performed in a monotonous version of his begging voice. One day a couple was having a quarrel in line. The woman said to her man, “You’re no writer!” and she pointed to John, “That’s a writer!” I won’t tell you that the man froze and nearly died because at that very moment John was reading from a story he had written himself and tossed into the trash. I don’t tell you that, because it really happened. Most unbelievable things really happen. Discarded drafts are easy to find because Park Slope citizens recycle scrupulously: paper bins hold only paper. There are a lot of writers in Park Slope.

New York John found the key that New Orleans John lost. Neither of them had an iPhone. In the future, when banks and other public buildings move into your phone, your (inconvenient) body will move to the internet. Only John will own anything “personal,” even though one of them stole it and the other one memorized it. If you want to be a person, you should rename yourself John. Your name will then be your password. While everybody is shedding their body and entering their iPhone (which they are going to lose) John will survive by being a clever egg with an eye and a mouth.

We are all transitioning to our phones now. When I take a walk I see people at various stages of losing body parts: people run into trees and driver-free cars, which helps them shed legs, heads and whatever soft body parts can be disposed of by hard things, but they are still a way from becoming pure internet. The devices they are indebted to facilitate their physical disintegration. Only John is still free, he has no password.

memory

There are two kinds of memory: remembering and forgetting. Human memory is fragile so it’s best entrusted to your iPhone. When you entrust your memory to the iPhone you must remember at all times where your phone is. You can spend every minute of the day trying to remember where your phone is. You have other devices to track your iPhone and you can, of course, ask someone to call your phone. Instead of memory you now have geographic anxiety. Anxiety reduces even the modicum of memory that you still have.

When you find your phone you must remember your password. You wrote your passwords with a pen on paper and hid the paper in a book in your library. You did this because you were afraid that “the dark web” might find your passwords and steal your money. You are sure to forget which book you hid your passwords in. Was it “The Birds of Venezuela?” No lo se. Eventually, all your memory will be in your iPhone. Because you prudently have, at some anxious point, entrusted the name of the book and pages where your handwritten passwords dwell to your iPhone, you must now spend all your time rifling through your library. You have 2,835 books. You didn’t check the mail today, so that number might be on the low side. Yes, but there is always the Cloud. Alas. The password for your Cloud is also on the hidden paper in the book. The Cloud has now all your thoughts, passwords, pictures, poetry and letters.

Your name is John. And that is also your password.

When you lose your memory and your phone, your flesh body will still be protected. But the more you forget, the more of your body gets dissolved by the “you” in the forgotten machine where the people you owe money to keep your memory. In the Cloud, they trade what you owe to entities that pay more than you owe. Your money is protected by passwords remembered by machines that are not your phone. You cannot lose money you don’t have. But the trades go on in your name, which is your password.

machines

There are two kinds of machines: machines for remembering and machines for forgetting. Your money and life are locked with a password in the remembering machine. But there is also the forgetting machine. This machine forgets the things you do not want to or need to remember, unpleasant things, like your childhood, your marital fights, your nightmares, your bad neighbors, your congressmen and the bad breath of fascism. The forgetting machine will forget these things for you, but also rids you of your pleasant memories. This is called “collateral damage.”

Whenever you remember something that you would like to forget you enter the password for the forgetting machine and, whoosh, the machine forgets it for you. If you forgot your password for the forgetting machine, you can buy a more sophisticated version that can intuit through an algorithm the things that you need or are compelled (by your debts) to forget, and it will do that without your intervention. This function is also in your lost phone, but you will never lose your ability to forget because the Cloud cares only about your assets. So there are two kinds of machines, one for remembering and one for forgetting. Do you remember which is which?

Now that we have gone all over that, can you please stop by the Co-op and say Hi to me while I read you a story?

Yours,

John